Few Australians are aware that their nation was once at the forefront of Space exploration and development. On the 29th of November 1967 Australia became the fifth country (third from its own territory) to launch a satellite. The WRESAT satellite was developed by the Weapons Research Establishment, Salisbury, South Australia and the Department of Physics at the University of Adelaide in South Australia. The project took less than a year from concept to launch.

The road to, and from, this launch has been somewhat winding. This is the story of that journey.

A Brief History of Australian space involvement

1940’s

Australia’s aeronautical and space activity in the 1940s was closely tied to its relationship with Britain, stemming from their shared defense and strategic interests during and after World War II. During the war, Australia’s role as a key Allied base in the Pacific and its vast, sparsely populated land made it ideal for testing military aircraft, radar, and other technologies. Britain, facing post-war economic struggles but determined to maintain its position as a global power, sought to leverage Australia’s geographic advantages for space-related activities. This collaboration was underpinned by shared scientific expertise and Australia’s loyalty to the British Commonwealth.

It is worth noting that during the 1940s, Australia’s aeronautical capabilities grew significantly due to the demands of World War II. The nation developed a robust aviation industry with companies like the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) and the Department of Aircraft Production (DAP) manufacturing military aircraft. We produced indigenous designs such as the CAC Boomerang fighter and the Wirraway trainer, and also built aircraft under license, including the Bristol Beaufort bomber.

—

July 1945 – Within the U.K. Ministry of Supply (MoS), a new Directorate of Guided Projectiles (DGP) under Sir Alwyn Crow, was created to control research and development of ship-and ground-launched weapons for the Admiralty and Army. By late 1945 it became apparent to Sir Crow and the defence planners that to test their new missiles a great deal of open land was required to establish a test range. The list of possible locations was soon narrowed to Canada and Australia, with Australia identified as offering the best mix of security, remote locality and generally favourable weather conditions including a dry climate and clear atmosphere.

September 1945 – The MoS reached out to the Australian Munitions Department representative in London, William Coulson who enthusiastically agreed to support this plan.

16th October 1945 – William Coulson returned to Australia and reported to his chief, Noel Brodribb, Controller General of Munitions. Also present were the three Chiefs of Defence Force Staff, Frederick Shedden, then Secretary of the Department of Defence ,John Dedman, and Sir David Rivett and Dr F. W. White of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR, later CSIRO).

The Minister for Defence, John Dedman, then briefed Prime Minister J. B. Chifley. The Crow-Coulson plan was subsequently recommend to Cabinet. Prime Minister Chifley strongly supported the project, as he believed that Australia clearly stood to benefit, provided an acceptable agreement could be worked out on how the control, work, costs and information were to be shared.

April 1946 – A mission from the U.K. led by Lieutenant-General JF Evetts CB CBE MC flew to Mt Eba homestead to carry out the first investigation for the suitability of the area for a guided missile range. His survey and mapping adviser was Colonel Lawrence Fitzgerald OBE, Director of Military Survey, Army Headquarters.

June 1946 – June 1946.- After considering Evetts report, the U.K. Commonwealth Defence Science Conference unanimously resolved that facilities should be provided as early as possible in Australia for the testing of guided projectiles and pilotless supersonic aircraft, and for the associated research and development including radio control and countermeasures

June 1946 – The first Dakota landed on the first temporary airstrip. A regular RAAF courier service was inaugurated which provided travel, food, mail and supplies for people who were inspecting the potential range.

20 Sept 1946 – The British Government dispatched a cablegram to Chifley supporting the establishment of the missile range.

Following for the Prime Minister from the Prime Minister. The United Kingdom Government have considered the report of Lt Gen Evetts’s Mission to investigate the possibility of providing facilities in Australia for research and development work on guided missiles and supersonic pilotless aircraft. We for our part agree with the recommendation of the Mission which has since been endorsed by the informal Commonwealth Conference on Defence Science that an experimental range and supporting development establishment should be set up in Australia. We also accept the recommendation of the Mission as regards the area to be used or the range. We should be glad to learn whether the Commonwealth Government are in agreement with these two recommendations. If so, we think that the first step should be to install the necessary facilities at the rangehead and along the first 300 miles of the range and that the remainder of the range area should be reserved for future use as and when required. For this purpose we should like, if you agree, to send Evetts to Australia again accompanied by a small technical staff to collaborate with the Commonwealth authorities concerned in the detailed planning and execution of the project. Evetts would serve in a civilian capacity . . .

19th November 1946 – Chifley referred the matter first to his Defence

Committee and then to Cabinet, where it was subsequently approved.

1st April 1947 – The Long Range Weapons Establishment (Woomera rocket range) came into existence as a Joint Project between Britain and Australia, as a British experimental land-based missile range. Early research primarily focused on missile development, including the development of missile-borne nuclear weapons. The Long Range Weapons Establishment subsequently became a cornerstone of Australia’s defence infrastructure and its collaboration with the UK in military technology.

24th April 1947 – The name Woomera selected for the new town associated with the rocket range.

22nd March 1949 – The first testing missile, a simple solid propellent 3 inch UP rocket, was launched from Range F at Woomera.

August 1949 – The first formal missile trial was undertaken at Woomera using captured German 4 inch LPAA, Taifun rockets, with WAF 1 fuel (aniline and furfuryl alcohol) and nitric acid oxidant.

1950’s

In the 1950s, Australia’s space launch activities were primarily focused on missile testing and early rocket development at the Woomera Test Range. During this period, Woomera became one of the most important missile testing sites in the world, largely due to the Anglo-Australian Joint Project with the United Kingdom. The decade saw the launch of several experimental rockets and missiles, including the Skylark and Long Tom rockets. These early launches were critical in laying the groundwork for later space exploration efforts, positioning Australia as a significant player in the emerging field of rocketry and space research. The 1950s activities at Woomera set the stage for the more advanced space launch operations that would follow in the 1960s.

—

1955 – The Weapons Research Establishment (WRE), the Australian defence scientific and technical research organisation initiated a High Altitude Research Project (HARP). The HARP vehicle was a rockoon, a combination of balloon and sounding rocket, based on a concept successfully utilised for upper atmospheric research in the US.

13th February 1957 – British scientists began using Skylark sounding rockets to study the upper atmosphere. The Skylark was a remarkably successful rocket and has been used for scientific research by many countries. Many Skylark rockets were fitted with a recoverable nosecone to allow the scientific instruments inside to be safely returned to earth.

Launch of a Skylark from Woomera’s Range E in 1957. It reached an altitude of about 129 Km.

The Skylark was an inexpensive, but very successful high-altitude research rocket developed by the Royal Aircraft Establishment in the United Kingdom. It used solid fuel to keep it simple and inexpensive.

For the same reasons, it was decided not to include a guidance system. Instead, it was fired from a Woomera launch tower made out of pieces of bridges left over from World War II.

In its initial form, the 7.62-metre long Skylark was designed to carry payloads of between 45 and 68 kg to a height of over 150 kilometres. A later two-stage version (length – 9.39 metres) could reach altitudes of up to 240 kilometres.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s, many Skylarks were launched from Woomera with payloads dedicated to Solar, X-ray and UV astronomy, as well as ionospheric research. Over the years, more than 200 Woomera-launched Skylarks carried payloads for British, European, German, and American space programs.

The last Skylark launch from Woomera occurred on 25 August 1987 as part of studies into Supernova 1987a in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

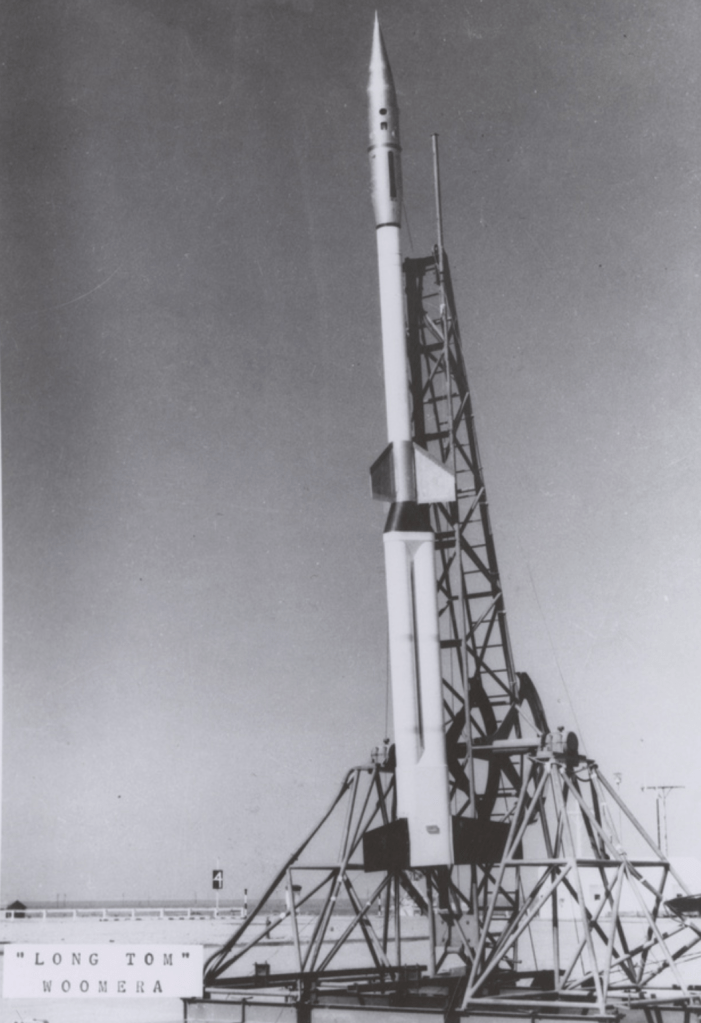

October 1957 – The first Australian-designed and built sounding rocket, the Long Tom, was launched at Woomera, using surplus British motors. The Long Tom was a two-stage 8.2-metre-long vehicle which could carry an array of scientific instruments that could be used to measure the temperature, density, pressure, composition, structure and movement of the upper atmosphere. In the early 1960s it was superseded by the HAD and HAT sounding rockets.

Long Tom

1958 – The Weapons Research Establishment (WRE) developed a second small vehicle for use in testing the Woomera Range instrumentation. Like its “big brother” Long Tom, Aeolus (named for the Greco–Roman god of the winds) it was assembled from surplus British motors. In this case a cluster of seven LAPStar motors for the first stage, with a single Mayfly as a second stage. With a less powerful boost stage, its apogee was not as high as that of Long Tom. But it was capable of carrying recoverable payloads.

7th September 1958 – The first Black Knight roared into Woomera’s skies from Launcher 5A on 7 September 1958, reaching an altitude of 225 kilometres. The ballistic test vehicle was developed by Saunders-Roe Ltd. in collaboration with the Royal Aircraft Establishment in the United Kingdom, to gather data as part of the development of Britain’s Blue Streak Intercontinental Ballistic Missile program.

Black Knight launch

The basic single-stage Black Knight was powered by a Gamma Mk. 201 rocket engine. The vehicle would attain a burnout velocity of over 12,000 km per hour at an altitude of about 113 kilometres. The nose cone would then separate, continue coasting to an altitude of about 800 kilometres, and then re-enter the atmosphere before being recovered. Total flight times were about 20 minutes.

Black Knight in cradle

1960’s

In the 1960s, Australia was actively involved in space launch activities primarily through the Woomera Test Range in South Australia. During this decade, Australia, in collaboration with the U.K., launched several rockets as part of military and scientific research programs. The most notable of these was the Blue Streak rocket, which was originally developed as a ballistic missile before being repurposed for space launches. Additionally, the 1960s saw the launch of the Black Knight and Black Arrow rockets, with Black Arrow successfully placing Australia’s first satellite, WRESAT (Weapons Research Establishment Satellite), into orbit in 1967.

—

24th May, 1960 – The sixth Black Knight took to the sky as a two-stage version with the nose cone being recovered after a successful mission. The second stage increased the velocity of re-entry to that expected for a Blue Streak warhead. When the Blue Streak program was cancelled in 1960, the two-stage Black Knight version was used for the Gaslight program which gathered data related to physical phenomena associated with high-speed re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

A two-stage version also was used in Project Dazzle – a joint Anglo-Australian-US program researching phenomena occurring during re-entry. Two-stage Black Knights used a more powerful Gamma MK. 301 rocket engine.

The single-stage Black Knight had an overall length of 10.16 metres, while the two-stage version was 11.6 metres long. The diameter was 0.91 metres with a span across the fins of 2.13 metres.

February, 1960, – The Governments of Australia and the United States of America formally agreed to cooperate in space flight programs being conducted by the US.

Australia undertook to establish and operate a number of tracking stations which would form part of a world-wide network under the control of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The Department of Supply was responsible for fulfilling the Australian commitment under this agreement. The construction and operation of these tracking facilities in Australia was financed by NASA. Management and operation were provided from Australian resources.

Island Lagoon was the first tracking station built outside the United States. It was originally one of the Deep Space Network stations used for spacecraft tracking. The site was first built as a mobile station, with the equipment and buildings mounted on trailers for easy relocation if necessary.

35′ – 0″ diameter dish at Island Lagoon, Woomera, 3 August, 1960

The location of the site near Woomera in the South Australian Outback provided a location relatively free from man-made radio frequencies, making it a noise free environment for receiving week signals from far away. The site employed approximately 110 people to run and manage the site.

The site also had an optical camera, called the Baker Nunn Camera. This unit was designed for the international Geophysical year in 1957 for observing and photographing stars and orbiting satellites. This camera started operating in 1958. Island Lagoon was operated for the Deep Space Network until it was shut down in 1972. Supported projects included Ranger, Mariner, Pioneer, Lunar Orbiter.

1960 – The Muchea Tracking Station received the telemetry and voice data over Australia when John Glenn orbited the Earth in Mercury rocket Faith 7, the first orbit of a man from the United States.

This tracking station was developed for Project Mercury, the United States mission to send people into space. The Muchea site was the only site outside the United States that was able to send commands to the spacecraft (all the other stations were used to collect data only).

This tracking station used VERLORT radar equipment to track spacecraft (Very Long Range Tracking) which was capable of tracking targets up to almost 4000 km away. The radars were capable of collecting telemetry information and voice contact between the spacecraft and the station. The tracking data was both stored on magnetic tapes and sent to Washington for analysis using teletype equipment and radio. The station was closed in 1963, as technology for tracking spacecraft improved.

1962 – ELDO – the European Launcher Development Organisation – was established to develop a satellite launch vehicle for Europe. Woomera, was chosen as the launch site for the test vehicles. The ELDO project originated back around 1960 with the cancellation of the British “Blue Streak” ICBM program. Blue Streak became the first stage of the “Europa” vehicle with France providing the second stage and Germany the third. Italy worked on the satellite project, while the Netherlands and Belgium concentrated on tracking and telemetry systems.

Australia was the only non-European member – a status granted in return for providing the launch facilities. Ten Europa rockets were launched from Woomera between 1964 and 1970, but no satellite was ever successfully placed into orbit using these rockets.

The launch site for ELDO’s Europa launch vehicles. Two launch pads were built on the shore of dry Lake Hart. Launcher 6A, in the foreground, was the only one completed and used for launches. Launcher 6B is visible in the distance. The Mobile tower at Launcher 6A is shown in its rolled back position. Today, the concrete remains, but the rest has long gone.

The ELDO project was divided into three phases.

- Phase 1 involved launching northwest toward Talgarno in Western Australia. Three successful launches (F-1, F-2 &F-3) of the first stage (Blue Streak) were conducted in 1964/65.

- Phase 2 saw northerly launches into the Simpson Desert in the Northern Territory. Launches (F-4 to F6/2) were conducted in 1966/67.

- Phase 3 involved northerly launches with the target of reaching orbit and eventually orbiting an operational satellite. Launches (F-7 to F-9) were conducted between 1967 and 1970. The Final F-10 flight never took place.

The final all-up launch of ELDO’s Europa 1 launch vehicle took place on 12 June 1970 with the satellite failing to reach orbit. European satellite launch activities then shifted to the French site at Kourou, in French Guiana, which is now home to Ariane launches.

1962 – The Weapons Research Establishment designed, built and conducted a number of high altitude density (HAD) experiments at Woomera using a two-stage HAD rocket. The two-stage HAD rocket consisted of a Gosling boost motor with a LAPstar rocket as its second stage. Each rocket ejected a 2m diameter inflatable radar-reflective spherical balloon at 130-Km high to fall at speeds of up to 3200 Km/hr until it collapsed at about 30-Km high. Analysis of radar measurements of the falling sphere produced data on air density and temperature as well as wind direction and speed.

1963 – Carnarvon Tracking Station (Western Australia), was built for the Gemini Program, the second step for NASA’s plan to put a person on the Moon. Replacing Muchea, it used some of the equipment from Project Mercury, but was a much larger complex. The station was closed in 1975.

June 1963 – December 1964 – Tidbinbilla (affectionately known as “Tid”) is the only active tracking station in Australia. When the site was officially opened in 1965 there was one 26 metre antenna, Deep Space Station 42, to support deep space probes and manned space flight missions.

Since this time, the station has grown to have 4 large antennas, including the largest steerable parabolic antenna in the southern hemisphere and now supports almost all the missions involved in interplanetary space exploration and exploration of the sun in Australia’s role in the Deep Space Network.

The station is situated on approximately 10 acres of land 40 kilometres outside Canberra. The valley has been carefully landscaped to control soil erosion and to maintain the area. There are approximately 130 people employed to run and manage the site. In the past there has been up to 160 people employed at Tidbinbilla. Projects: Manned Missions (Mariner, Apollo etc) Deep Space Missions (Voyager, Galileo, MGS etc).

November 1964 (official opening in 1966) – Orroral Valley Tracking Station had equipment to allow voice transmission to and from astronauts, reception of telemetry (spacecraft data) and television from spacecraft. It also had a large radar for spacecraft positioning, STADAN (Satellite tracking and data relay network) network facilities and an accurate timing system. The station employed approximately 180 staff members to manage and run to site.

This tracking station was built to support the STADAN network (Space Tracking and Data Acquisition Network. This project had an emphasis on global mapping, planetary composition and orbital observatories. The antenna and other related equipment could transmit and receive signals to Earth orbiting satellites about positions, velocity and performance. The site was designed with the capacity to be redeveloped or adapted to be used for other space programs.

The station was located about 40 kilometers from Canberra on an area of approximately 40 acres. The location of the site in a valley protected the station from man made radio waves (such as radio noise) which could interfere with the reception of radio signals from satellites. There was approximately 110 people employed to manage and run the site when fully operational. In December 1985, Orroral Valley tracking station was closed as part of a consolidation of NASA facilities in Australia. Project: STADAN Earth orbiting satellites.

Orroral did not have the capability for direct voice communications to astronauts until the space shuttle in 1981. In January 1981 a team from Orroral went to the laser site at Yarragadee (this site is still operational for laser ranging) near Geraldton WA to install an antenna and system for voice only communications to the Space Shuttle to help cover a gap in the orbit.

The mission controllers for the Space Shuttle placed very great importance on maintaining voice contact with the astronauts. When amateur radio operators at Orroral learned that one of the astronauts (W5LFL) was going to take a hand-held amateur radio on STS-9 in 1983, they proposed a test to see if this could be used as a backup voice link back to Houston. A temporary radio station (VK1ORR) was built at the Deakin Switching Centre in Canberra and the test was successful. Photos are on the CD and it was the cover story of Electronics Today International in March 1984.

Orroral did not support Mercury, Gemini, Ranger or Apollo except for the Apollo/Soyuz mission project in 1975 when American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts linked vehicles in Earth orbit and carried out joint experiments in space. There was also some limited support of the ALSEP packages on the moon in later years. (Orroral was the station that eventually commanded them off.)

Orroral did not have a radar, either large or small. It did have ranging systems that worked in conjunction with normal telemetry and command equipment such as the Goddard Range and Range Rate (GRARR) and S-Band Ranging Equipment (SRE). It also had a high power laser ranging system under the auspices of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Institute of Harvard University, Boston. (This may have been confused in some sources as radar. Carnarvon station that closed in 1974 did have FPQ6 radar and supported some of the missions mentioned above.)

The Baker-Nunn was re-located to Orroral in about 1982/3 and after Orroral closed it was donated to Siding Spring astronomical Observatory.

Orroral had a number of telemetry systems and could receive data from up to a maximum five different satellites in different positions simultaneously.

The WRESAT satellite was tested at Orroral prior to launch in 1967.

In 1982 Orroral antennas were: 1 – 26M (85′) dish receiving on 136MHz, 400MHz, 1700MHz, 2200MHz; 1 – 9m (30′) dish for both up & down link 2200MHz USB; 2 – SATAN receive antennas at 136MHz; 1 – 9 yagi antenna at 136 MHZ; 2 SATAN command antennas at 150MHz; 1 – 6m (20′) dish for uplink on 2200MHz USB; 1 – minitrack system on 136MHz; 1 – yagi system for monitoring radio emissions from the planet Jupiter, 1 – Turn Around Ranging System (TARS) for GMS satellites. After closure the 26m antenna was donated to the Uni of Tas and is now located in Hobart.

At one point Orroral was the largest tracking station outside the United States and Australia had the greatest number of tracking stations outside the United States.

1965 – 1966 – Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station was built for the Manned Space Flight Missions, and managed by the Goddard Space Flight Centre. It was designed to provide reliable tracking and communications during the lunar voyage, orbit, landing and return. “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind!”. These exultant words uttered by Niall Armstrong as he stepped out onto the moon in 1969 were received at this tracking station in Australia.

The station had a 26 metre steerable antenna capable of moving very quickly to allow tracking of a spacecraft travelling at very high speeds. The antenna had transmission and reception capacities, including the ability to receive television signals. The station occupied a 14 acre site, 32 km from Canberra and was operated by approximately 100 staff members.

In 1974, at the conclusion of the Skylab program and termination of the Manned Space Flight activities, Honeysuckle Creek joined the Deep Space Network as DSS 44. When Honeysuckle Creek closed in December 1981, the 26 metre antenna was relocated to Tidbinbilla and renamed DSS 46, where it is used for spacecraft positioned close to Earth. Projects: Apollo, DSN.

May – September 1966 – The Cooby Creek mobile tracking station was set up as a mobile tracking station for the ATS Project. The ATS project was part of NASA’s scientific investigations of Near Earth Satellites. The main objective of the project were test flights of satellites for meteorological, navigation and communication purposes and to study different types of orbits around the Earth such as stationary orbits. The site was constructed between May and September 1966 at a total cost of over 5 million dollars, with operating costs of one million dollars a year for the five year life span of the site.

The station was set up as a mobile tracking station, that is all equipment was on trailers as was easily disassembled to allow the site to be moved if required. The antenna on site was a 12 metre antenna which had the capacity to transmit and receive voice, high speed data, teletype and colour TV signals.

The site (approximately 15 acres) was positioned outside Toowoomba in the Darling Downs, Southern Queensland, in a secluded valley to protect the station from man made radio frequencies (such as radio signals) which could effect the received data. The site employed about 100 staff to run and maintain the tracking station. The Tracking Station was shut down in 1970.

16th August 1968 – In 1968 the Australian designed, two stage Kookaburra rocket carried small instrument packages called dropsondes to the upper atmosphere. These were released from the rocket and measured atmospheric temperature, pressure and ozone content as they fell to earth on a parachute. The Kookaburra was launched 33 times in total before being retired in 1976.

29th November 1967 – in 1967 Australia became the fifth country (third from its own territory) to launch a satellite. The WRESAT (Weapons Research Establishment Satellite) project had followed on from an existing program of upper atmospheric research using sounding rockets. The satellite was developed by the then Weapons Research Establishment (Salisbury, South Australia) and the Department of Physics at the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

The project took less than a year from concept to launch. The Redstone launch vehicle used had been left over from the SPARTA project – a joint U.S., U.K., and Australian research program aimed at understanding re-entry phenomena.

WRESAT launch

The U.S. Department of Defence donated the modified Redstone vehicle and the services of the TRW vehicle preparation team, while the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) supplied global tracking and data acquisition services. Facilities of the Joint Australia/United Kingdom Weapon Testing Project supported the launch activities.

The goals of WRESAT

- Extend the range of scientific data relating to the upper atmosphere;

- Assist the U.S. in obtaining physical data of relevance to its research programs;

- Develop techniques relevant to the launching trials in the ELDO and British satellite programs;

- Demonstrate an Australian capability for developing a satellite using advanced technology and existing low-cost launch facilities at Woomera.

WRESAT statistics

- Height of satellite: 1.59 metres

- Base diameter: 0.76 metres

- Mass: approx. 45 kilograms

- Length with 3rd stage motor: 2.17 metres

- Orbital Mass with 3rd stage motor: approx. 72.6 kilograms

1967 -In 1967 Philip Chapman was the first Australian-born astronaut. He was selected in the second group of NASA scientist astronauts. He worked as support crew through the Apollo Moon landing series until 1971 and was never assigned to a flight, as NASA funding cutbacks terminated the Moon shots, and substantially cut back the planned follow-on Skylab and Apollo Applications flights.

28th June 1969 – The Black Arrow was designed and built by Great Britain as a satellite launch vehicle. Only four were launched – all from Woomera. The first (28 June 1969) was deliberately destroyed following loss of control 50 seconds into the flight. The second (4 March 1970) was a successful sub-orbital flight. The third (2 September 1970) was the first orbital attempt which ended in failure when the second stage engines shutdown 13 seconds early.

The Woomera launch of the British Prospero satellite by a Black Arrow launch vehicle on October 28, 1971

At 0409 GMT on October 28, 1971, the fourth and final Black Arrow left its launch pad at Woomera and placed the Prospero satellite (International designation: 1971-093-A) into an orbit inclined at 82 degrees to the equator about 10 minutes after liftoff. The initial orbit had a perigee (low point) of 537 kilometres and an apogee (high point) of 1,593 kilometres. (As of 10 May, 2004, Prospero’s orbit was 529 by 1,337 kilometres and the satellite had completed nearly 62,600 orbits.)

The Black Arrow program was cancelled by the British Government in July 1971, although one further launch was permitted.

The Prospero satellite was built by the British Aircraft Corporation. It was spin-stabilized and was designed to prove basic systems for future satellites. It carried a single scientific experiment designed to detect micrometeoroids.

1970’s

In the 1970s, Australia’s space launch activities continued at the Woomera Test Range, though the focus shifted from large-scale missile testing to more specialized satellite launches and scientific research. This decade saw the decline of the British-Australian missile collaboration, but Australia remained active in space-related activities, including supporting international satellite launches. One of the key events was the launch of the European Launcher Development Organisation’s (ELDO) Europa rocket series, which used Woomera as a testing ground. Although the Europa program faced challenges and was eventually canceled, it highlighted Australia’s ongoing role in global space efforts. The 1970s also saw increased interest in utilising Woomera for international collaborations, laying the groundwork for future space partnerships and activities.

—

23rd January 1970 – OSCAR-5, also known as Australis-OSCAR-5 (An amateur radio satellite), was designed and built by students in the Astronautical Society and Radio Club at the University of Melbourne. AMSAT managed launch of the satellite January 23, 1970, from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, to a 925-mile-high polar orbit aboard a Delta rocket ferrying an American weather satellite to space.

1st July 1970 – The Joint Defence Space Communications Station (JDSCS) was activated at Nurrungar, approximately 19 Kilometres or 12 miles from Woomera within an area of 130 square kilometres (32000 acres) called the Nurrungar Prohibited Area. The first US Air Force personnel arrived in January 1971. The JDSCS was renamed the Joint Defence Facility Nurrungar and is a joint Australian-United States venture. The mission of the JDFN and the Defence Support Program is to provide a highly available, survivable and reliable satellite-borne surveillance system to detect and report missile launches, space launches and nuclear detonations in real-time.

15th October 1972 – OSCAR-6 another amateur radio satellite had been built in the U.S., West Germany and Australia. It was launched to a 900-mile-high orbit alongside a U.S. government weather satellite on October 15, 1972. The satellite’s two-way communications transponder received signals from the ground on 146 MHz and repeated them at 29 MHz with a transmitter power of one watt. Low-power ground stations with simple antennas were successful in using the satellite.

15th November 1974 – OSCAR-7 yet another amateur radio satellite was launched November 15, 1974. It was a second Phase-2 satellite, similar to OSCAR-6, but with improvements. For instance, OSCAR-7 had two transponders. One received at 146 MHz and repeated what it heard at 29 MHz while the other listened on 432 MHz and relayed the signals on 146 MHz. The latter had an eight-watt transmitter and was built by radio amateurs in West Germany. In the first satellite-to-satellite link-up in history, a ham transmitted to OSCAR-7 which relayed the signal to OSCAR-6 which repeated it to a different station on the ground. Australians built a telemetry encoder for the satellite and Canadians built a 435 MHz beacon.

1974 – In 1974, the CSIRO established Australia’s first digital image processing facility for remotely sensed data. With new noise removal and contrast enhancement procedures, the CSIRO was able to produce high quality, digitally enhanced photographic products, optimised for the display of geological information. These images were marketed to industry in the late ’70s, in one of CSIRO’s early commercialisation ventures. The same concepts were then used to define the specifications for the Australian LANDSAT receiving station, which allowed Australian users much faster access to satellite data. In 1984, a CSIRO team, which, through innovative signal processing, developed a simple, low-cost upgrade to the LANDSAT station at Alice Springs so that exploration companies, agricultural and environmental users could obtain digital images of the next generation of LANDSAT data.

The CSIRO team (Andy Green, Ken McCracken and Jon Huntington) behind much of this work won the Australia Prize in 1995, for their pioneering work in satellite remote sensing in Australia. The successful application of this technology to mineral exploration was established and continues through collaborative research projects sponsored by the Australian Mineral Industries Research Association (AMIRA).

1980’s

In the 1980s, Australia’s space launch activities experienced a decline in direct rocket launches from the Woomera Test Range, shifting focus toward satellite communications and space support services. This decade marked the successful deployment of the AUSSAT series of satellites, beginning with AUSSAT A1 launched in 1985, which significantly enhanced the nation’s telecommunications, broadcasting, and data services. Australia also played a crucial role in supporting international space missions through its network of tracking stations, providing vital communication links for agencies like NASA during pivotal missions, including Space Shuttle flights and deep space explorations.

—

1980 – Officially opened in 1980, the Canberra Space Centre began it life as a display of images and models relating the work of the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (Tidbinbilla Tracking Station).

1982 – Australia’s national satellite company, AUSSAT Proprietary Ltd., in May 1982 selected Hughes Communications International, a wholly owned subsidiary of Hughes Aircraft Company, to develop the country’s first satellite program. Under the contract, Hughes Space and Communications Group (SCG) has built three satellites and two telemetry, tracking, command and monitoring (TTC&M) stations. Also provided are launch and operational services and ground support. Both Hughes units are today a part of Boeing Satellite Systems, Inc. (BSS).

The spin stabilized 376, an established communications satellite design, was chosen for Aussat. The first two Australian satellites were launched on the space shuttle in August (Aussat A1 -> Optus A1) and November 1985 (Aussat A2 -> Optus A2). The third was launched in September 1987 (Aussat A3 -> Optus A3) on the Ariane 3 rocket.

August 1984 – CSIRO Office of Space Science and Applications (COSSA) founded in August 1984. There have been four COSSA engineering programs: RADIOASTRON (a Russian-led orbiting radio telescope, currently awaiting launch), ATSR (Along-Track Scanning Radiometer), the APS (Atmospheric Pressure Sensor), and the airborne imaging spectrometer (which CSIRO later supported in privatised form, SpIN 76).

1984 – Paul Scully-Power was the first Australian-born astronaut to get into space. He was on a one-off flight, as a Payload Specialist on Mission 41-G in 1984. He used to work as an oceanographer with the Royal Australian Navy Research Lab, but left Australia many years before his flight. It was a secret military mission to test a radar-means of detecting the surface wakes of submerged Soviet nuclear submarines.

1988 – AUSSAT Proprietary Ltd became the first customer to purchase the Hughes 601 body-stabilized satellite in July 1988, when it ordered two of the high-powered spacecraft to be delivered on orbit for its next-generation system.

1989 – CSIRO addmitted to the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS).

1990’s

In the 1990s, Australia’s space launch activities were relatively quiet, with a continued focus on satellite operations and supporting international space missions rather than direct launches from Australian soil. The country maintained its critical role in global space efforts through its tracking and communication facilities, such as the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, which supported NASA and other international space agencies. During this decade, Australia also began exploring opportunities to revitalise its space industry, including discussions on developing a domestic space agency and increasing commercial space activities. Although no major launches occurred within Australia during the 1990s, the groundwork was being laid for future developments in the space sector.

—

1991 – AUSSAT was sold to a consortium (which included Cable & Wireless, plc) and now provides domestic and international telecommunications services as Optus. Pursuant to the Telecommunications Act 1991 (“1991 Act”), Optus was authorized to compete as a facilities-based carrier with Telstra in the Australian domestic and international sectors. The 1991 Act also affirmed the role of AUSTEL as Australia’s telecommunications regulator, with policy set by the Ministry of Communications and the Arts.

The Optus B series ordered in 1998 by AUSSAT were considerably more powerful and versatile than previous satellites. Optus B is three times more powerful than and will last twice as long as Aussat A. The Optus B satellites enhanced existing satellite communications services throughout Australia, including direct television broadcast to homesteads and remote communities, voice communications to urban and rural areas, digital data transmission, high-quality television relays between major cities, and centralized air traffic control services.

In addition, Optus B1 introduced the first domestic mobile satellite communications network to Australia. The satellites are equipped with a 150-watt L-band transponder to permit mobile communications through small antennas mounted on cars, trucks, and airplanes. This mobile ability extends throughout the nation. The satellites also use high-powered spot beams covering the major cities to provide such specialized services as high-performance data links, videoconferencing, and a range of other dedicated services, including direct broadcast for pay television.

The first Optus B satellite was launched on a Chinese Long March 2E booster August 14, 1992, from Xichang, China. The second was destroyed in an explosion during launch on a Long March 2E December 21, 1992. After seven months of investigation, both Hughes and the Chinese concluded that a cause for the explosion could not be determined. Immediately after the loss, Hughes began work on another satellite, Optus B3, which was successfully launched Aug. 28, 1994. More information on the Optus B series can be found on the Boeing Satellite Systems site.

July 1995 – The Earth Observation Centre (EOC) was created.

1996 – In Woomera the Japanese Aerospace Laboratory (NAL) and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) conducted their Automatic Landing Flight Experiment (ALFLEX) project trials to gather data for a planned Japanese “space shuttle”.

May 1996 – Dr Andy Thomas an Australian-born astronaut was named as payload commander for STS-77 and flew his first flight in space on Endeavour.

20th August 1996 – In the 1996 Budget Statement, the Minister for Science and Technology, the Hon. Peter McGauran announced the start of a small demonstration project; i.e. Federation Satellite 1 (FedSat). In early 1996, the Minister had considered a draft proposal for a new national space agency. The proposal was poorly recieved, so another approach was tried. Given that funding was scarce, the initiative was linked to the Centenary of Federation in 2001 program. The prevailing administrative arrangements for space were also changed.

17th October 1997 – Under a unique arrangement between Hughes Global Services, PanAmSat Corporation, and the Australian Defence Force, a Hughes-built communications satellite formerly used by the U.S. Navy is providing new communications services to the Australian Defence Force. Leasat 5 began limited service to the Australian Defence Force on Oct. 17, 1997. Leasat 5 will provide ultra high frequency satellite communications services to the Australian Defence Force for five years, if all options are exercised.

1997 – JP 2008 – MILSATCOM The MILSATCOM project will provide satellite communications capabilities to support future ADF strategic and tactical communications needs. The project is structured as five major Phases.

Phase 1 comprised of a study and various activities in support of Phase 2.

Phase 2 is concerned with the near term provision of a mobile tactical satellite communications capability for land, sea and airborne mobile communications. Phase 2 of the major project JP2008 MILSATCOM provides for three distinct satellite communications capabilities:

- Phase 2A – the Defence Mobile Communications Network (DMCN) Capability; DMCN is intended to make maximum use of the civilian infrastructure and will introduce a satellite-based secure communications system, using the Cable and Wireless Optus L-Band service. The Initial capability was provided by procurement of commercial MobileSat terminals using the standard commercial Optus (now Cable and Wireless Optus) MobileSat service. Rockwell Australia developed and produced kits to install the terminals in land based military platforms and transportable containers. The equipment for the Initial capability was successfully deployed on Exercise K95 and valuable lessons were learned about the use of modern commercial equipment in a military environment. The Interim capability, which entered service in November 1996, comprises: leased hub station capacity at Cable and Wireless Optus earth stations in Sydney and Perth minimally modified to meet Defence requirements; terminals for limited land mobile applications; and a small number of terminals for specified ship applications

- Phase 2B – Aircraft Capability (P3C and C130H); and

- Phase 2C – an Offshore Satellite Communications Capability (MOST) (Delivered).

Phase 3 is aimed at the provision of a more comprehensive satellite communications capability including a Defence satellite payload and supporting ground infrastructure. Phase 3 of the MILSATCOM Project comprises five discrete projects (sub phases) which interlink to provide an overall satellite capability. It will support Defence satellite communications needs at a regional level pending the introduction of an enhanced military satellite capability under Phases 4 and 5.

- Phase 3A – Future ADF Satcom Architecture; A System Feasibility Study to identify the ADF user requirement/capability post 2005 and potential satellite communication solutions was completed in December 1997

- Phase 3B – Project Definition Study: Under this phase, a study will be conducted to define system architecture and equipment specifications for the most suitable satellite communications system identified under Phase 3A to be implemented under Phases 4 and 5 of the MILSATCOM Project. This sub-phase is scheduled to be considered for approval in 2002/03 prior to the commencement of Phase 4 and 5 activities.

- Phase 3C – approved in November 1998 – Capability Technology Demonstrator (CTD) – Theatre Broadcast System (TBS); This project phase is a Concept Technology Demonstrator (CTD) for a Theatre Broadcast capability. The CTD will be used to refine the requirement for equipment to be acquired under Phase 3E. The Theatre Broadcast system concept is based on the US Global Broadcast System GBS. It employs high bandwidth to broadcast information to users and a narrow bandwidth return channel to place information requests. This architecture lends itself to the provision of Internet like services, which share an asymmetric bandwidth architecture. The request channel need not necessarily be over the same satellite transponder or even over the satellite, as the required bandwidth is sufficiently low that narrow band systems such as HF radio could be employed.

- Phase 3D – Australian Defence Satellite Communications Capability (ADSCC); Under JP2008 Phase 3D, the acquisition of a Defence satellite payload as part of a shared commercial/Defence satellite platform. Phase 3D will provide a substantially increased satellite communications capacity with extended offshore coverage and a dedicated Defence-operated payload control facility in Australia. It will provide for communications in three frequency bands, UHF, X and Ka, two of which (X and Ka) have not previously been available under ADF control. The increased communications capacity will enable the ADF to support and develop modern C3I systems and will also offer a greater prospect of Interoperability with Australia’s allies. 3D was approved in December 1997, a contract was awarded in October 1999 and the satellite is expected to enter service in late 2001.

- Phase 3E – Ground Infrastructure for the Defence Payload on Optus C1 Satellite. JP 2008 Phase 3E was approved in June 2000. It will provide SATCOM terrestrial infrastructure to support netted, broadcast and full duplex services to higher priority platforms and deployable headquarters. The infrastructure will include the Advanced SATCOM Terrestrial Infrastructure System (ASTIS) and modifications/upgrades to legacy systems. Phase 3E will only provide the minimum SATCOM infrastructure required by Commander Australian Theatre (COMAST) for use with the Defence payload on the Optus C1 satellite. Infrastructure beyond the minimum will be procured under other projects

Phase 4 and Phase 5 are unapproved. They involve the acquisition of a more comprehensive military satellite communications capability in the latter part of the next decade. JP2008 is a Category 1 project (over $200m) and the Project Office has been split into two System Program Offices (SPOs), Space and Terrestrial.

10th July 1997 – The Minister for Science and Technology, the Hon. Peter McGauran announced an initial program grant of $20 million for the building of core FedSat project through a new Cooperative Research Centre for Satellite Systems (CRCSS). A necessary part of the CRCSS context was industry participation and contribution of $36 million over a seven year timeframe.

Core CRCSS Participants

- University of South Australia

- CSIRO

- Queensland University of Technology

- Auspace Limited

- University of Technology, Sydney

- Vipac Engineers and Scientists Limited

- University of Newcastle

Supporting CRCSS Participants

- Defence Science and Technology Organisation

- La Trobe University

- Codan Qld. Ltd.

- DSpace Pty Ltd

- Curtin University of Technology

Corporate, government and individual sponsors of the Cooperative Research Centre for Satellite Systems and the FedSat project can be found at this URL FedSat Support Program. The CRCSS partners include strong representation from the space industry (and the former ARIES consortium). The CRCSS has research and development, education and training, engineering and project management functions. The CRCSS is to have a broader role than FedSat, covering the long-term strategic operational and commercial role for satellites.

| FedSat was designed as a small, 50 kg satellite intended for a polar orbit at an altitude of 500 to 1000 km with a 70-degree inclination to the equator. It was equipped with multiple payloads, including a magnetometer for space physics experiments, advanced solar cells for in-orbit testing, a GPS receiver for scientific research, and systems for remote sensing, communications, and computing. The satellite was based on a proven space platform to minimize development risks, with local testing conducted prior to its planned launch. To keep costs low, FedSat was considered for launch as a piggyback payload on a Japanese Space Agency (NASDA) rocket. The development of FedSat was a collaborative effort involving multiple partners. Private companies, Auspace and Vipac led the assembly and testing of the satellite, while other contributors included Mitec, Space Innovations Limited, D-Space, and Optus, which provided key technologies and expertise. The Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) played a significant role in the project, as did several academic institutions. The main teaching and research laboratories were located in Brisbane at the Space Industry Development Centre for Satellite Navigation at the Queensland University of Technology, and in Adelaide at the Institute for Telecommunications Research at the University of South Australia. FedSat’s development was coordinated by the Cooperative Research Centre for Satellite Systems (CRCSS), which brought together public and private entities to advance Australia’s capabilities in space technology. Despite challenges such as funding constraints and partner transitions, the project successfully culminated in the satellite’s launch on 14 December 2002, marking a major milestone in Australia’s space exploration efforts.  FedSat-1 |

| ARIES, the Australian Resource Information and Environment Satellite was a commercial project for worldwide geological exploration and mapping by a remote sensing satellite. The vehicle was to be a small 480 kg satellite in polar orbit used for specialised remote sensing with a two-dimensional image, multiple narrow channel, single instrument. It was to have much higher image capacity compared to the existing Spot or Landsat systems. With an ability to re-image sites weekly and a three-year life, the craft would have used proprietary satellite platform and programs. The ARIES consortium had many members including CSIRO, Auspace and the Australian Centre for Remote Sensing. Other companies involved include Earth Resource Mapping, Geoimage and Technical and Field Surveys. With support from Macquarie Bank and Australian Taxation Office allowances, the consortium completed a $1.2 million feasibility study in 1997 and had aimed to launch in 2000, possibly before FedSat. |

1997 – The Australian Space Research Institute (ASRI), the Cooperative Research Centre for Satellite Systems (CRCSS) and the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) entered into a joint venture to design, construct, launch and operate a microsatellite by 2001 (now 2002). Initially labelled the Joint Australian Microsatellite (JAMSAT), the project is now recognised as the Joint Australian Engineering Satellite (JAESAT). Renaming was required due to a title clash with the existing Japanese amateur microsatellite project.

2nd December 1997 – MILSATCOM indicated that it would establish a Australian Defence Military Communications Payload on the proposed new Optus C1/D satellite planned to be launched in late 2000. It was intended to enhance the capacity and coverage of satellite communications ensuring essential communications are available at critical times during operations. Until this capability was developed Defence had relied on satellite services through leasing agreements with commercial providers. The MILSATCOM package was intended to provide a significant enhancement with the major benefits being a greater area of coverage and the use of the less congested military communication bands.

1st January 1998 – Marked the official start of CRCSS operations. The CSIRO Office of Space Science and Applications (COSSA) had undertaken development of the program and establishment of the CRCSS in Canberra. In January 1998, the core of COSSA staff transferred to the CRCSS.

June 1998 – Dr Andy Thomas returned to earth in June 1998 after 5 months aboard the Mir space station. All NASA employees, such as astronauts, are civil servants, and US civil servant must be US citizens. The US requires renouncement of most former nationalities, including Australian. So by definition, Australians are not eligible to apply to become astronauts. The only way is to be sponsored at Government level, and Australia has never shown any interest in that. Indeed Australia had two opportunities in the early 1980s, when the Shuttle launched AUSSAT A1 & A2 satellites. The Australia Government declined the US offer, as it couldn’t find the fees required to pay for the passengers’ safety training. It is likely that every other country that had a communications satellite launched by the Shuttle took up the offer of the “free” seat.

21st December 1998 – The SPACE ACTIVITIES ACT 1998 No. 123, 1998 was assented.

24th October 1999 – Cable & Wireless Australia subsidary Optus awarded Space Systems/Loral and Mitsubishi Electric a contract to build a high-powered communications satellite for Optus and the Australian Department of Defence.

2000’s

In the 2000s, Australia’s space activities focused more on satellite services, space research, and supporting international missions rather than launching rockets from its own soil. The country continued to play a vital role in global space communications through facilities like the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, which supported NASA’s missions, including the Mars rovers and deep space probes. Domestically, there was increased interest in space-related research, leading to the formation of organizations like the Cooperative Research Centre for Satellite Systems, which developed the FedSat satellite, launched in 2002. This period also saw the rise of private sector involvement in space-related industries, laying the foundation for the eventual establishment of the Australian Space Agency in 2018.

—

2000 – Optus announced the development of the Optus C1, a third-generation system designed to replace an existing spacecraft in the Optus communications constellation, and to provide additional, enhanced capabilities when launched in 2002. Cable & Wireless Optus, then a major Australian telephone and communications company, intended to use Optus C1 to provide distribution for video, direct-to-home TV, and telephony and Internet connections to remote areas. The area of fixed satellite services coverage was to include Australia, New Zealand, and Asia. Optus C1 would also provide communications services for the Australian Defence Forces.

Optus C1, a high-powered model in SS/L’s 1300 geostationary satellite bus family, was intended to carry 18 antennas and four payloads: a Ku-band payload for the commercial mission, and UHF, X-, and Ka-band payloads for the defence tasks. Total power on the satellite, designed to operate for 15 years, was to be approximately 11kW at end of life. Optus C1 will have a launch mass of nearly five metric tons.

As of 2nd November 2000, Optus had four satellites in orbit and nearly half a million Australians had a dish pointed at its B3 Hotbird satellite.

2000 – FedSat project delays caused by Space Innovations Limited (SIL) reacquisition by management, after a brief ownership by SpaceDev Inc. Despite these challenges, SIL’s expertise in satellite platforms was instrumental in providing the foundational technology that enabled FedSat’s eventual success.

2000 – The Joint Australian Engineering Satellite (JAESat) project, initiated in the early 2000s, aimed to develop a micro-satellite for educational and technological demonstration purposes.

However, due to cost and schedule overruns with the Cooperative Research Centre for Satellite Systems (CRCSS) FedSat Project, CRCSS was forced to withdraw funding support for JAESat. In response, the JAESat consortium, led by the Australian Space Research Institute (ASRI), re-scoped and reorganized the project to target a mid-to-late 2002 launch using a Dnipro-1 (Dnepr) launch vehicle, a repurposed SS-18 SATAN ICBM. The consortium, in collaboration with Suzirya (Ukrainian Youth Aerospace Association), worked to complete the system design, fabrication, and testing.

Despite these efforts, the project faced ongoing challenges, including funding shortages and technical obstacles. As a result, JAESat was ultimately never launched, leaving its objectives unfulfilled.

2000 – The Australian Resource Information and Environment Satellite ARIES-1 project was formally closed February 2000. The ARIES-1 consortium consisted of Australia’s CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation); Auspace Ltd (a subsidiary of the European Matra Marconi Space Group); ACRES (Australian Centre for Remote Sensing); Earth Resource Mapping Pty Ltd; Geoimage Pty Ltd; and Technical and Field Surveys Pty Ltd. The project was being funded by the ARIES consortium partners, the Australian Government (through its new Space Policy Unit) and an international group of mining and exploration companies and national geological mapping agencies.

8th December 2000 – SACE in SPACE launched as a joint initiative by the Northern Adelaide Regional Workplace Leaning Centre Inc (narwlc) and the University of South Australia, Institute for Telecommunications Research (ITR). Students, looking to study Mathematics and Physics, were chosen to work on entry level skills, supporting the research being done on the FedSat satellite under construction by the Co-operative Research Centre for Satellite Systems (CRCSS), at ITR. It ran for 18 months, 1 day a week. During this course students learning about satellite orbits, Signals and noise, transmitters, antennas, radio waves, mobile communications etc.

2000 – BLUEsat (Basic Low Earth Orbit University Satellite) was an educational satellite project initiated by students at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia. Launched as a hands-on, student-led initiative, BLUEsat aimed to design, build, and operate a small satellite capable of conducting basic scientific and engineering experiments in low Earth orbit.

The project served as a platform for students to gain practical experience in aerospace engineering, systems design, and satellite operations, while also promoting interest in space technology within the academic and broader Australian community. Although BLUEsat faced challenges and did not achieve an actual launch, it played a significant role in training future engineers and fostering collaboration between students, academics, and the space industry.

1st January 2001 – The Space Activities Regulations 2001 (Statutory Rules 2001 No. 186) were established under the Space Activities Act 1998 to regulate space-related activities in Australia. These regulations commenced upon their publication in the Government Gazette, as specified in Regulation 1.02.

The regulations outlined the framework for licensing and oversight of space activities, including the construction and operation of launch facilities, launch permits, and liability provisions. They aimed to ensure public safety, protect the environment, and fulfill Australia’s international obligations regarding space operations.

In 2018, the Space Activities Act 1998 was repealed and replaced by the Space (Launches and Returns) Act 2018, leading to the repeal of the 2001 regulations. The new legislation introduced updated regulatory measures to accommodate advancements in space technology and industry practices.

8th-21st, March 2001 – Dr Andy Thomas third flight was on STS-102 Discovery which was the eighth Shuttle mission to visit the International Space Station.

On 23rd May 2001 – The Australian Government and the Government of the Russian Federation signed the Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes. The Asia Pacific Space Centre (APSC) an Australian company established to build, own, operate, and market a commercial space centre has secured exclusive worldwide marketing rights for the Russian AURORA launch vehicle. AURORA will be capable of delivering satellites up to 12 tonnes to low earth orbit and of 4.5 tonnes to geosynchronous transfer orbit.

APSC’s Russian technical partners include the Russian Aviation and Space Agency (Rosaviakosmos), RSC Energia, the State Research and Production Space Rocket Centre (TsSKB Progress) and the Design Bureau of General Machine Building (KBOM). RSC Energia’s distinguished history includes the initiation of the first human space flight by Yuri Gagarin on 12 April, 1961. TsSKB Progress manufactures the highly successful Soyuz family of launch vehicles. More than 1600 Soyuz rockets have been launched, with a success rate of some 99 percent. KBOM has more than forty years experience in developing and operating rocket launch facilities.

APSC’s project has the strong support of the Australian Government, which has granted it Major Project Facilitation Status as well as put in place a statutory and regulatory approvals framework. It is also strongly supported by the Government of the Russian Federation. Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov signed a decree on 10 March 2001 approving APSC’s project.

June 2001 – Controversy was raised over Optus’ future. At issue, whether the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) will approve a $14 billion takeover bid from the Singapore Government’s telecommunications company SingTel. A number of powerful players have lined up with some powerful arguments, both for and against SingTel’s offer. A major concern has centred on the fear that once in control of Optus and its satellites, Singapore could use the network to uncover security secrets.

Seven Network owner Kerry Stokes had opposed the takeover in a submission to the FIRB, saying he has “grave concerns” about Australia’s secondlargest telco being effectively controlled by a foreign government. “SingTel is not a company, it’s a government,” he said.

24th June 2001 – The Minister for Industry, Science and Resources, Senator Nick Minchin, and Minister for Regional Services, Territories and Local Government, Senator Ian Macdonald, announced that the Government has agreed to provide up to $100 million to pave the way for the Asia Pacific Space Centre (APSC) to establish a spaceport on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean.

The Government will be providing $100 million to support the project through the Strategic Investment Incentives programme. This includes provision of common use infrastructure on Christmas Island in the form of an upgrade to the airport and a new port and road and assistance with spaceport infrastructure such as ground station facilities for telemetry and tracking.

APSC has committed a minimum of $15 million out of its operational receipts over the first 5 years of launch operations towards the establishment of a Space Research Centre. The Centre would be a partnership between APSC and Australian universities to support and sponsor research, teaching, and technical and managerial capacities in the Australian space industry.

Russian launch technology will be protected in Australia under a Technology Safeguards Agreement currently being negotiated between the Australian and Russian governments, consistent with the commitments of both countries under the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). The Agreement will strictly circumscribe the control and use of the launch technologies.

11th July 2001 – Cable & Wireless Optus announced a seven-year deal to monitor the Pacific Ocean Region by satellite for the international Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), the organisation with global responsibility for the Treaty, and UK-based HOT Telecommunications have set up an International Monitoring System (IMS) of over 320 monitoring stations throughout the world. Under the terms of the seven-year contract with HOT, Optus will support and operate a communications hub for the Pacific Ocean region, collecting data from over 60 monitoring stations.

September 2001 – AUSLIG merged with AGSO – Geoscience Australia to form Geoscience Australia, the national agency for spatial information.

23rd Oct 2001 – SingTel Australia Completed its Acquisition of Optus.

30th October 2001 – An attempt to test the world’s first flight test of supersonic combustion scramjet Hyshot at Woomera failed owing to a problem with the Terrior Orion rocket which lifted the payload to about 100 kilometres instead of the planned 300+ kilometres. This project is an international consortium led by University of Queensland researchers was attempting a scientific and engineering challenge to test a hypersonic ramjet or scramjet. Researchers hope to mount a second flight in 2002.

06th December 2001 – Optus announced that Optus and SingTel would create three new integrated business units (IBUs) which will result in greater efficiency and improved customer service. Previously run as separate operations, both companies’ respective International Satellite, International Carrier and International Network businesses will combine. The three IBUs will be responsible for the SingTel Group’s operations globally.

The new International Satellite Business IBU will be managed from Australia and will operate throughout the Asia-Pacific region, while the International Network and International Carrier Services IBUs will be managed from Singapore. The new International Satellite Business IBU will operate and manage five satellites covering Asia, Australia and New Zealand; 13 satellite earth stations; three Tracking, Telemetry and Control facilities; as well as agreements that allow access to 25 satellites across the region.

17th December 2001 – The Optus $500 million ‘C1’ satellite will be launched on an Ariane rocket from French Guiana in the fourth quarter of 2002. A 13m Mitsubishi dish (originally installed in Hobart – as part of the Aussat major city earth station project) has been installed at Optus’s satellite earth station at Belrose in Sydney.

30th July 2002 – The HyShot Flight Program achieved supersonic combustion on its second flight.

13th December 2002 – A Japanese H-2A rocket carried the research pod FedSat into ordit. Japan had offered to put Australia’s satellite into space as a gift for the centennial anniversary of Australia’s commonwealth government.

The 58-kilogram (120-pound) FedSat has high-tech communication, space science, navigation and computing equipment and was intended to help bring broadband Internet services to remote parts of Australia. Data from its three-year mission was to be shared between the two nations.

FedSat is the first satellite built in Australia since WRESAT and Oscar V in the period 1967-1970. The satellite was built by a team of about 15 engineers and scientists at the CRCSS Project Office at Auspace Limited in Mitchell, a suburb of Canberra. Most of the payloads were developed in other CRCSS laboratories in NSW, Queensland and South Australia. The United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration supplied one payload.

FedSat departed Canberra on the 30th of October and arrived in Tokyo on 31 October. It arrived at Tanegashima Space Centre on 5 November afer a journey by truck and ferries. FedSat has been prepared for launch and on 21 November was mated with the payload support structure of the H-IIA rocket.

2009: Australia began significant participation in the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project, an international effort to build the world’s largest radio telescope, with portions of the array located in Western Australia.

2010: The Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex played a critical role in supporting NASA’s Mars rover missions, including the successful landing of the Curiosity rover on Mars.

2013 – Gilmour Space Technologies was founded by brothers Adam and James Gilmour in Queensland, Australia. The company initially focused on hybrid rocket technology, which combines solid and liquid propellants for safer and more cost-effective rocket launches.

2016: Australia’s NovaSAR-1 partnership with the UK was established, involving a radar satellite that provided data for environmental monitoring, including forest mapping and disaster response.

2018: The Australian Space Agency (ASA) was officially launched on July 1, marking a significant milestone in Australia’s space capabilities. The ASA’s mission is to triple the size of the space industry to $12 billion by 2030 and create 20,000 new jobs.

31st August 2018: The Space (Launches and Returns) Act 2018 replaced the outdated Space Activities Act 1998 to modernize Australia’s regulatory framework for space activities. It governs launches, returns, and related operations conducted by Australian entities or within Australia, including the use of rockets, satellites, and high-altitude balloons. The Act introduces a simplified licensing system with permits and authorizations for various activities, such as Launch Permits and High Power Rocket Permits, while ensuring compliance with international treaties like the Outer Space Treaty (1967). By updating liability requirements and risk management protocols, the legislation protects public safety and aligns Australia’s space operations with global standards.

The Act was specifically designed to reduce regulatory burdens, fostering innovation and encouraging growth in Australia’s space sector. It provides clearer pathways for startups and smaller missions, supporting the development of a competitive commercial space industry. Since its introduction, the Act has enabled an increase in space activities across the country, including commercial satellite launches and the development of local launch sites. It positions Australia as a key player in the global space industry, balancing the need for industry growth with safety, sustainability, and international responsibility.

2019: Australia signed an agreement with NASA to collaborate on the Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the Moon and eventually send them to Mars. This partnership included a $150 million investment by Australia to support the development of lunar technologies.

2020: The ASA supported the Southern Hemisphere Space Studies Program in collaboration with the International Space University, focusing on developing skills and knowledge in space policy, law, and management.

2020: The SmartSat Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) was launched, focusing on developing advanced telecommunications, Earth observation, and space systems, positioning Australia as a leader in smart satellite technologies.

2021 – The ASA and NASA deepened their collaboration with the signing of the Joint Statement of Intent, reinforcing Australia’s role in the Artemis Accords and space exploration missions.

2021 – CSIRO launched the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), which provided the most detailed view of the southern sky, contributing to global astronomical research.

2021 – Gilmour Space signed an agreement with the Australian Space Agency to collaborate on launching Australian payloads into space, including defense and scientific missions.

2022 – The ASA announced the Moon to Mars initiative, a $150 million program to support Australia’s role in NASA’s Artemis mission, focusing on the development of new technologies for lunar exploration.

2022 – The Binar-1 CubeSat, developed by Curtin University, was launched, marking the first satellite of the Binar Space Program aimed at supporting space research and development in Australia.

2023 – Australia’s Kanyini satellite, developed by South Australian company Inovor Technologies, was successfully launched, aimed at Earth observation and improving data for agricultural and environmental monitoring.

2023 – Gilmour Space successfully completed multiple tests of its rocket engines and components, bringing the company closer to its first commercial orbital launch.

2024 – The SpIRIT satellite, a joint project between the University of Melbourne and Italian Space Agency, was set for launch. SpIRIT is Australia’s first space mission designed to operate in both Earth’s orbit and deep space, focusing on advanced scientific research and technology demonstration.

As of 5th November 2024 Gilmore Space (see programs below) announced that it had received a launch permit from the Australian Space Agency for the first flight of its Eris small launch vehicle. The launch is slated to occur before Christmas.

Eris small launch vehicle

Satellites

There have only ever been a handful of Australian-made or owned satellites (and a few more satellite projects that weren’t successful):

However, as of late 2024, Australia operates a diverse array of satellites serving various purposes:

Communications Satellites:

- Optus Satellites: Optus manages a fleet of geostationary satellites, including Optus D1, D2, D3, and Optus 10, providing communication services across Australia and New Zealand.

- Optus C-series

Optus C1 – Currently comprising a single Space Systems / Loral LS 1300-series satellite, it was partially funded by the Australian Defence Department. Optus C1’s use is shared between Defence and Telecommunications, in particular the supply of Television services to Australia. Mitsubishi Electric was the prime contractor responsible for manufacturing all the Optus C1 communications systems.

- Optus D-series

Optus D1 The satellites of the Optus-D series replaced and expand the services provided by the B1 and B3 satellites respectively, which had both been operating beyond their design lifetimes. The D1 satellite was launched on 13 October 2006 via an Ariane 5 ECA rocket, serving clients like the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), SBS, and Sky Television New Zealand. It supports broadcasting and VSAT users, with Kordia leasing a full transponder for New Zealand’s Freeview service. During testing, the New Zealand spot beam was mistakenly configured with horizontal polarization instead of the expected vertical polarization, causing service transfer issues for Sky Television. Sky later resolved this through a software update to its set-top boxes, enabling reception of horizontally-aligned signals and restoring their original capacity allocation by July 2007.

Optus D2 was launched on 5 October 2007 from the Guiana Space Centre using an Ariane 5 GS rocket. Positioned at 152° East, the satellite features 24 active Ku-band transponders, including sixteen 150W transponders and eight 44W transponders, with a launch mass of 2375 kg. D2 replaced the 13-year-old Optus B3 and continues to provide extensive broadcasting services, including a large number of Free-To-Air channels, many of which are in languages other than English.

Optus D3 followed on 21 August 2009, launched aboard an Ariane 5 ECA rocket from Kourou, French Guiana, and is located at 156° East. With 32 Ku-band transponders (twenty-four 125W primary and eight 44W backup) and a launch mass of 2500 kg, D3 is co-located with Optus C1 to enhance broadcasting capabilities. The satellite supports Foxtel’s High Definition programming, expanded digital services, and improved picture and sound quality, with 25% of its transponder capacity allocated to Foxtel for delivering new channels and services.

Optus 10, launched on 11 September 2014 from the Guiana Space Centre aboard an Ariane 5 ECA rocket, is positioned at 156° East in geostationary orbit. Manufactured by Space Systems Loral (SSL) using the LS-1300 satellite platform, it has a launch mass of 3200 kg and is equipped with 32 Ku-band transponders, including twenty-four 125W primary and eight 44W backup transponders. The satellite was commissioned on 21 March 2011, with Optus CEO Paul O’Sullivan announcing its role in enhancing satellite communications for the region.

Optus 10 provides high-quality broadcast services to households, along with two-way voice and data communication services across Australia and New Zealand. It supports government departments, premium businesses, and broadcasters such as FOXTEL, ABC, SBS, the Seven Network, Nine Network, Network Ten, Globecast Australia, and Sky TV New Zealand. This satellite plays a crucial role in delivering reliable communication and broadcast capabilities throughout its coverage area.

- Sky Muster Satellites: Operated by NBN Co, Sky Muster I and II deliver broadband services to remote and regional areas, enhancing internet connectivity nationwide.

Earth Observation Satellites:

- Digital Earth Australia (DEA): While not owning satellites, DEA utilizes data from international satellites to monitor environmental changes, supporting resource management and disaster response.

Defense Satellites:

- Wideband Global SATCOM (WGS): Australia collaborates with the U.S. Department of Defense on the WGS system, contributing to and benefiting from this global satellite communication network.

Research and Development Satellites:

- WESTPAC – formally known as the Western Pacific Laser Tracking Network (WPLTN) satellite, launched in July 1998 and is a commercial Australian communications and geodetic research satellite owned by Electro Optic Systems Pty Limited (EOS), Queanbeyan, NSW (New South Wales).

- CubeSats and Small Satellites: Australian universities and research institutions have launched several small satellites for scientific research and technology demonstration. Notably, in August 2024, three Australian-made satellites—Kanyini, Waratah Seed, and CUAVA-2—were launched as part of SpaceX’s Transporter-11 mission.

Older Satellite Programs

- Australis-OSCAR 5 – Australia’s first satellite and the only successful Australian amateur satellite, made in 1966 but not launched until January 1970.